How Do Routers Decide What Segments to Push onto a Packet in Segment Routing?

In a segment-routed network, nodes can push one or more segments onto a packet to create a precise forwarding path. If a packet simply follows the shortest path, then Junos OS decides the correct segment automatically. If the path involves traffic engineering (TE), then you can configure the segments manually or calculate them automatically according to your TE constraints. You can also use a centralized controller to calculate this information.

Prequisite Knowledge

We assume that the readers have read the topics titled What Is Segment Routing and Source Packet Routing in Networking?, What Features and Designs Does Segment Routing Enable?, and What Is Source Routing in a Segment Routed Network?, along with the prerequisites for these topics.

In a segment-routed network, Junos OS determines the SR-MPLS or SRv6 segments required to create forwarding instructions through a combination of automatic calculation and manual configuration. Paths can utilize a single MPLS label or SRv6 address, or a stack of segments.

This document briefly introduces you to all of the options. These options are then explained in greater detail in separate documents. This document uses SR-MPLS examples, but you can apply the same concepts to SRv6.

SPF Shortest Paths and Flex Algo Shortest Paths

If your only requirement is for traffic to follow the IS-IS or OSPF metrically shortest path to a remote router, then Junos OS simply uses the segment associated with that instruction. This happens automatically and is true for both regular topologies and Flexible Algorithm (Flex Algo) topologies.

In the case of the default complete topology, Junos OS will have a full mesh of SR tunnels in its inet.3 table (for SR-MPLS) or in its inet6.3 table (for SRv6).

Recall that the inet.3 and inet6.3 tables store all of the operational label-switched paths (LSP) that ingress on this device. By default, this table is used by BGP as a potential way to resolve BGP protocol next-hops. Every tunnel in these tables contains information about the shortest-path segment that must be pushed onto the packet to transport the traffic to the destination of the tunnel.

If you choose to enable any Flex Algo topologies in your network, then Junos OS also creates a separate full mesh of LSPs for all devices inside that topology. Depending on how you enable this feature, each topology can have its own equivalent of an inet.3 table on each Junos OS router, with a full mesh of shortest-path tunnels to every other router in the topology.

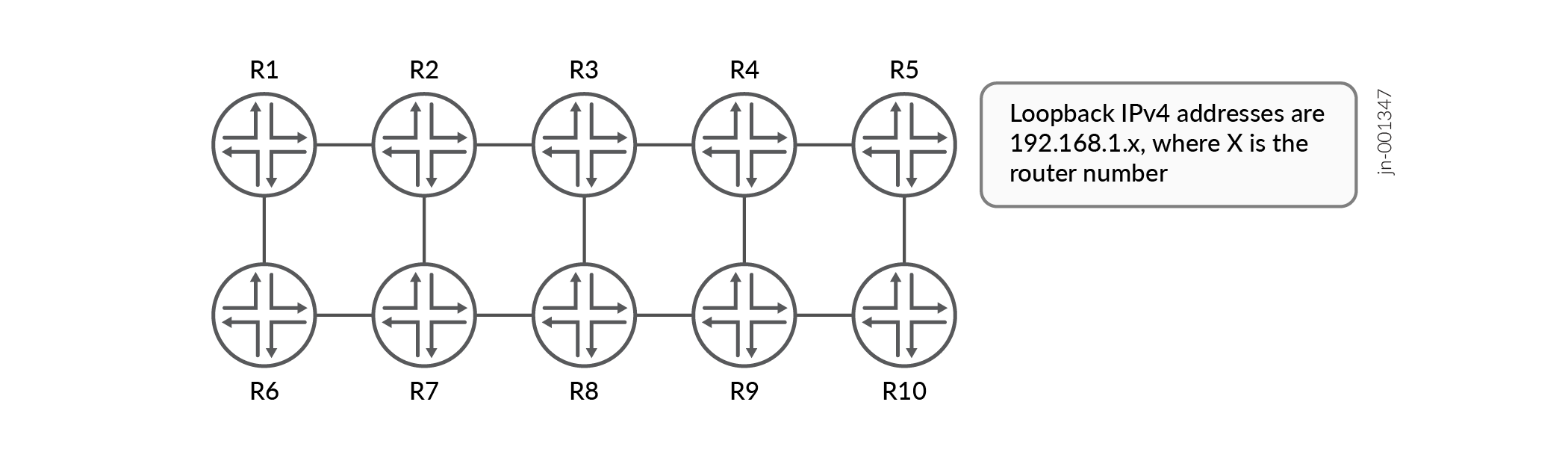

To understand this concept, see Figure 1 and CLI output 1 below. First, Figure 1 shows a network of ten routers, numbered from R1 to R10. Each router has a loopback IPv4 address of the format 192.168.1.x, where X is the router number.

CLI output 1 below focuses on router R1's inet.3 routing table after you enable a basic SR-MPLS deploymenton all devices. It shows a full mesh of LSPs to every other device in the network. If you configure shortest path segments on each node in your network, then this full mesh of tunnels is created automatically on every SR-MPLS device.

Output 1: After enabling a basic SR-MPLS deployment on all routers, R1’s inet.3 table shows a full mesh of label-switched paths to all other routers

user@R1> show route table inet.3

inet.3: 9 destinations, 9 routes (9 active, 0 holddown, 0 hidden)

+ = Active Route, - = Last Active, * = Both

192.168.1.2/32 *[L-ISIS/14] 00:06:45, metric 100

> to 10.1.2.2 via ge-0/0/0.0

192.168.1.3/32 *[L-ISIS/14] 00:02:18, metric 200

> to 10.1.2.2 via ge-0/0/0.0, Push 300403

192.168.1.4/32 *[L-ISIS/14] 00:02:18, metric 300

> to 10.1.2.2 via ge-0/0/0.0, Push 300404

192.168.1.5/32 *[L-ISIS/14] 00:02:18, metric 400

> to 10.1.2.2 via ge-0/0/0.0, Push 300405

192.168.1.6/32 *[L-ISIS/14] 00:06:45, metric 100

> to 10.1.6.6 via ge-0/0/2.0

192.168.1.7/32 *[L-ISIS/14] 00:02:18, metric 200

to 10.1.2.2 via ge-0/0/0.0, Push 300407

> to 10.1.6.6 via ge-0/0/2.0, Push 300407

192.168.1.8/32 *[L-ISIS/14] 00:02:18, metric 300

> to 10.1.2.2 via ge-0/0/0.0, Push 300408

to 10.1.6.6 via ge-0/0/2.0, Push 300408

192.168.1.9/32 *[L-ISIS/14] 00:02:18, metric 400

> to 10.1.2.2 via ge-0/0/0.0, Push 300409

to 10.1.6.6 via ge-0/0/2.0, Push 300409

192.168.1.10/32 *[L-ISIS/14] 00:02:18, metric 500

> to 10.1.2.2 via ge-0/0/0.0, Push 300410

to 10.1.6.6 via ge-0/0/2.0, Push 300410

Each of these LSPs contains a single outgoing transport label. The label represents the instruction to follow the shortest path to that remote router. SR-MPLS calculates the automatically and requires no additional configuration on R1.

For example, the output contains an ingress LSP to R5 with a destination address of 192.168.1.5. If R1 learns a BGP prefix with a protocol next-hop of 192.168.1.5, R1 resolves the prefix to this LSP. Therefore, R1 automatically uses the shortest-path segment associated with that tunnel. In this case, R1 pushs a single SR-MPLS transport label of 300405. This is the label that R2 receives when the you send traffic down the shortest path towards R5.

Topology-Independent Loop-Free Alternate Backup Paths and Microloop Avoidance

A similar automatic result takes place when you enable Topology-Independent Loop-Free Alternate (TI-LFA) or when you run microloop avoidance. In addition to segments that represent the shortest path to a remote device, segment routing also offers segments that forward traffic directly from one specific router to a next-hop neighbor. By combining shortest-path segments and direct next-hop segments, you can create any arbitrary path in the network. This approach prevents temporary loops that can occur during network convergence events. TI-LFA uses these two segment types to calculate and build backup paths.

When SPF calculates the best path to a destination link or router, TI-LFA reruns SPF to determine a backup path that protects against local link or neighboring router failures. Once TI-LFA calculates the path, it automatically decides the segment stack required on this path. This stack can range from a single shortest-path segment to a more complex series of hop-by-hop instructions. Either way, this happens without any additional user intervention.

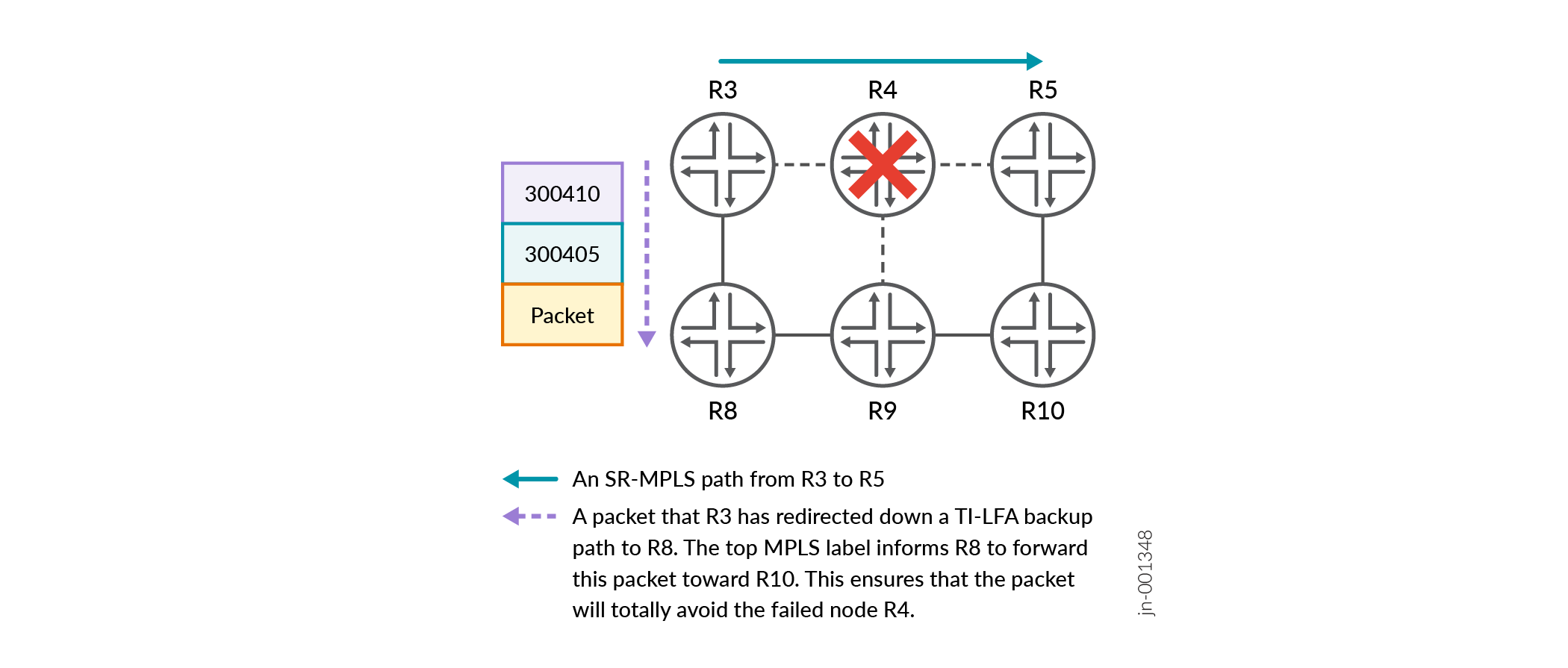

Figure 2 shows six routers where R4 has failed.

In a TI-LFA network, R3 is prepared for this event by calculating a backup path that routes around R4. However, R3 has also identified that R8 and R9 are both potential sources for a loop. To avoid this problem, R3 automatically pushes a second segment onto the packet that instructs the network to send the traffic to R10. From R10, the packet can then safely be delivered to R5. These segments are calculated and pushed automatically and require no additional user intervention beyond enabling TI-LFA. The same is true of microloop avoidance. In the event of a topology change, SPF calculates a new best path. If microloop avoidance detects the potential for a brief microloop on the new path, then Junos OS automatically pushs the necessary segments onto the packet that ensures that the packet reaches its destination.

Traffic Engineering with Manual User Segment Configuration

Junos OS offers several methods for determining the segments written to a packet for a traffic-engineered path. The simplest, but least scalable, method is for a user to manually create a tunnel to a remote router and then configure the MPLS labels or SRv6 addresses required for that path. In this case, the router does not actually check whether the segments are valid and correct. A few segments are not advertised at all, and cannot be verified for accuracy. In this case, Junos OS simply follows your instructions and writes whatever you specify to the packet.

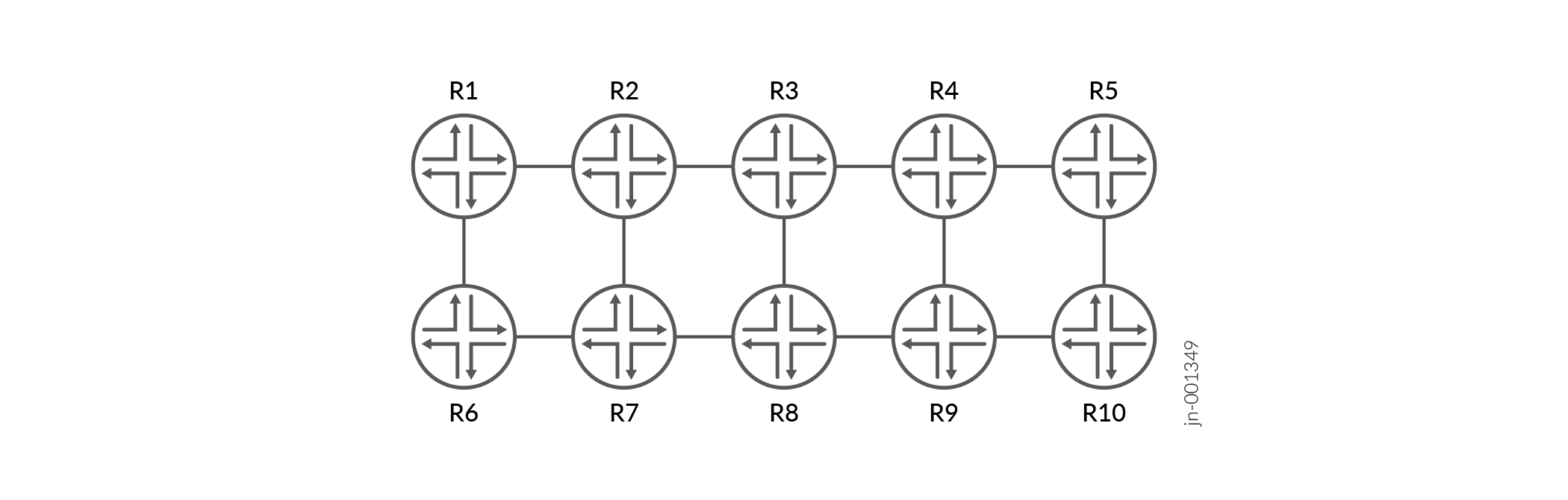

Figure 3 shows an example of this. Using the same topology of 10 routers, it introduces you to a Junos OS configuration construct called a segment list. By defining a named segment list, you can define the precise segments that should be written to a packet. You can then refer to the segment list when you create an SR-TE label-switched path.

The example uses SR-MPLS, but the concept is identical for SRv6.

protocols {

source-packet-routing {

segment-list PATH_R1_R5_EXPLICIT_LABELS {

HOP_1 label 1004012;

HOP_2 label 1004023;

HOP_3 label 1004034;

HOP_4 label 1004045;

}

}

}

This method is easy to configure but, like all static paths, cannot react to topology changes. If one of the links or nodes represented by your segments fail, then the entire path fails. Another disadvantage of this option is that it cannot inherently identify failures along the path. However, you can enable a new version of Bidirectional Forwarding Detection (BFD) called Seamless BFD (S-BFD) that actively monitors the path. This shuts the path down when a failure is detected enabling you to move over to another backup or secondary path.

Traffic Engineering With Manual User Configuration and IP Lookups

A more scalable method of traffic engineering is to configure the required IP hops that the traffic engineered path must take. For example, a path can combine loopback IP addresses and network interface addresses of the devices in the path. Junos OS can then convert these addresses into shortest-path instructions and direct next-hop instructions, and then calculate the required MPLS label or SRv6 address for that segment.

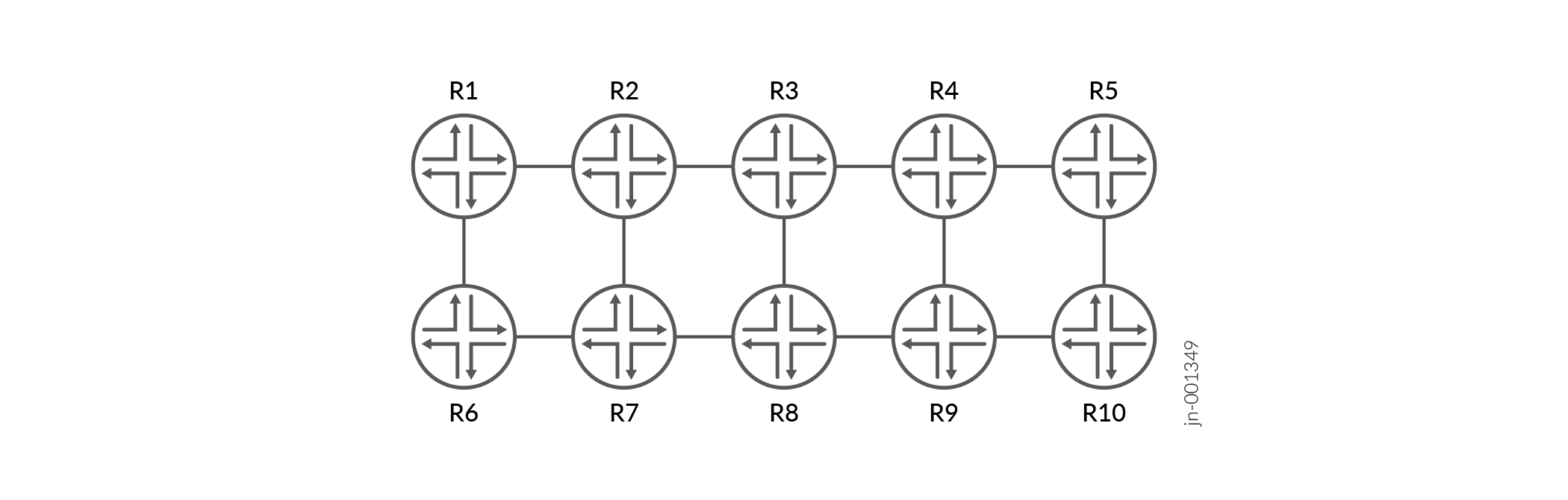

Figure 4 demonstrates this concept.

protocols {

source-packet-routing {

segment-list PATH_R1_R10_INTERFACE_IP {

auto-translate;

HOP_1 ip-address 10.1.6.6;

HOP_2 ip-address 10.6.7.7;

HOP_3 ip-address 10.7.8.8;

HOP_4 ip-address 10.8.9.9;

HOP_5 ip-address 10.9.10.10;

}

}

}

This is similar to the example in Figure 3 except that this time, the named segment list refers directly to interface IP addresses and loopback IP addresses. When this segment list is used in an SR-TE LSP, Junos OS automatically converts the IP addresses to the required segments. Note that this method still requires you to define the path manually. As such, this path cannot respond to the failure of any of the devices in this path. Nevertheless, the automatic translation of IPs to segments does introduce a small amount of dynamic behavior when compared to defining the segment values explicitly in your configuration.

Traffic engineering With Dynamic Path Calculation

An even more scalable method is to calculate the path dynamically based on a set of traffic engineering constraints. Junos OS will then calculate the correct segments for the calculated path. This option uses a version of the Constrained Shortest Path First (CSPF) algorithm used by RSVP. The algorithm is called Distributed CSPF (D-CSPF). The name reflects the fact that the protocol can be run on any router in the network. This is in contrast to the option of using a centralized controller.

D-CSPF offers some TE constraints found in RSVP, such as admin groups and shared risk link groups. Additionally, it includes segment routing-specific constraints, like limiting the maximum number of segments pushed onto a packet or exclusively using links that support local repair. D-CSPF can also consider alternative shortest-path metrics, such as TE metrics or delay metrics. Junos OS collects a set of constraints together into an object called a compute profile. This set of constraints can then be applied consistently to any TE path that requires those constraints.

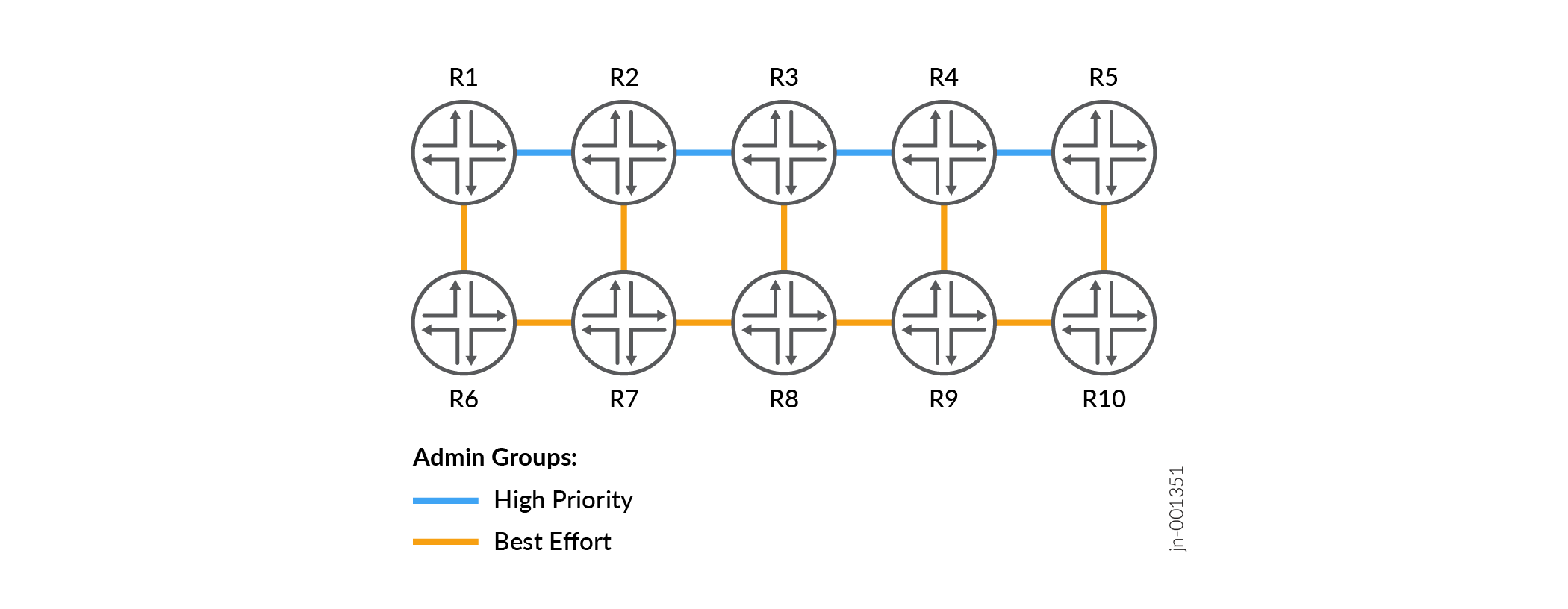

Figure 5 briefly introduces this concept.

protocols {

source-packet-routing {

compute-profile ONLY_USE_HIGH_PRIORITY {

admin-group include HIGH_PRIORITY;

maximum-segment-list-depth 6;

metric-type {

te;

}

}

}

}

The Figure 5 shows that each link in the network has been tagged with one of two admin groups, called HIGH_PRIORITY and BEST_EFFORT. The diagram also shows the configuration for a basic compute profile, which calculates a path that only considers links that are tagged with the admin group HIGH_PRIORITY. This example also shows that you can include other traffic engineering constraints inside one compute profile object. After defining a compute profile, you can use this object in two ways. The first option is to reference it inside a tunnel with a destination endpoint that you have manually defined. In this case, although the endpoint is configured manually, everything else is calculated dynamically by Junos OS, including the path and the segment list. If the topology changes, Junos OS automatically calculates a new path and a new segment list. The second option is to reference the compute profile as part of an On Demand Next-Hops (ODN) deployment. This feature does not require you to manually define each tunnel endpoint. Instead, Junos OS can dynamically build new tunnels to any valid BGP protocol next-hop.

In both cases, the result is that Junos OS decides the segments that should be written to a packet.

Traffic engineering with a Centralized Controller

You can use a central controller to calculate and create a segment list. A controller also offers you all of the TE options mentioned earlier: creating manual paths with explicit segments or IP hops, and dynamic paths based on TE constraints. In addition, controllers offer a variety of powerful features, such as topology visibility, graphical path visibility, bandwidth constraints, and TE between routing domains. Once the controller determines the path that a tunnel should take, the controller finds the segments associated with that path, and then writes this information directly to the data plane of the ingress router for the path. The path can easily cross a domain boundary. The ingress router does not need to be aware of every single segment in the path. The ingress router need to know only the MPLS labels or IPv6 addresses that should be written to the packet, along with the direct next-hop for the traffic.

Further reading

The above sections are a few basic concepts of Segment Routing Traffic Engineering. Stay tuned for detailed documentation updates for Segment Routing Traffic Engineering in upcoming revisions.

If you have read all four topics in this introductory series on segment routing, then you are now ready to explore SR-MPLS and SRv6 in detail.